Feeding the Mind with Carolyn Steel

Can food be used to define what constitutes a good life? And with that, two underlying questions pop up: How should we eat? How should we live?

| Carolyn Steel, architect and the author of two acclaimed books “Hungry Cities” and “Sitopia” about urban food systems, delivered a keynote lecture while the Hungry EcoCities consortium gathered in Turin on November 28th, 2023 for the Knowledge Transfer Event. Her speech was affective and thought-provoking: using food to define a good life, through the lenses of history, ecology, technology, philosophy and beyond. |

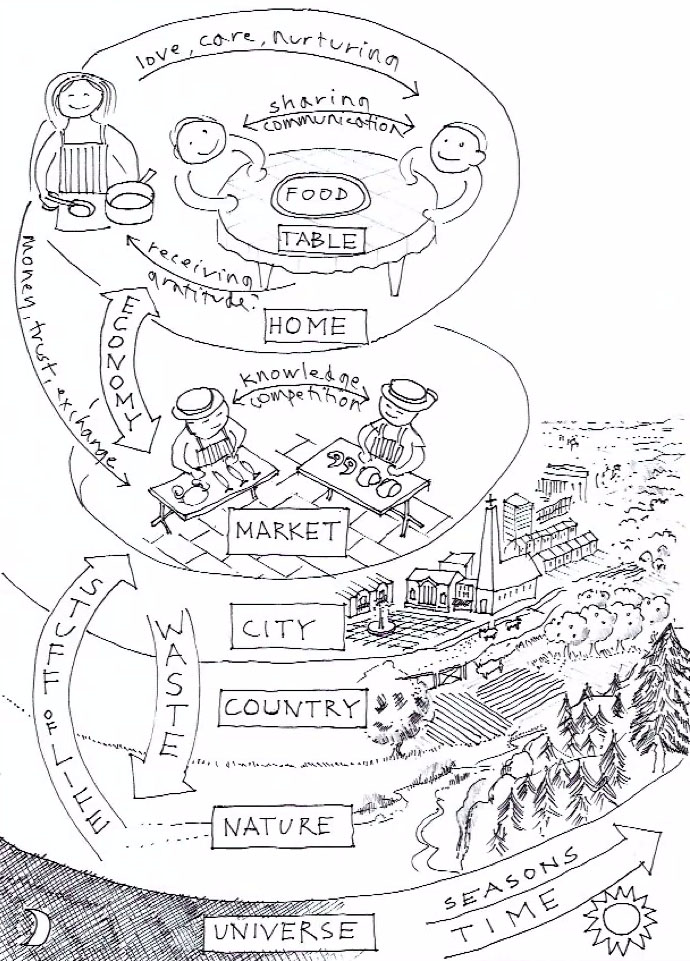

These ideas resonate with the principles and directions outlined in Hungry EcoCities, given that our project derived its name from her work and first book. Much like the Humanizing Technology Experiments presented at the Knowledge Sharing Event, Carolyn highlighted the significance of shared meals and the intricate relationship between humans, food, and the environment. Carolyn uses the word Sitopia – ancient Greek for “foodplace” (sitos = food; topos = place) – to encapsulate such dynamics. Cities are nurtured by food because it shapes our bodies, emotions and habits, as well as economy, architecture, the climate and other factors crucial to our well-being.

The question of how to eat is as old as the human race is. All living creatures need food, and as humans, we evolved through using different forms of technology to eat better. Carolyn traced this process of development through history in her presentation. As one of the most important points, the invention of more advanced means of transportation allowed us to send food to places far from where it is grown. From that point onwards, we were no longer required to stay in close proximity to our food sources, and were able to expand the boundaries of the urban spaces we lived in.

Carolyn sees a shared meal as the best economy we can create since food has inherent, fundamental value. This is supported by Aristotle and his perspective on the relationship between the city and the countryside. There is a natural limit to how much food people can eat, while people would always like to have more money. To find a balance, it might be interesting for contemporary societies to use food as a measuring metric for the economy.

Another key concept discussed in the presentation was food miles, introduced by Tim Langes. It refers to how far the ingredients of a dish came from, a query that is also investigated in various Humanizing Technology Experiments, such as Low Carbon Climate Cookbook and MVP x FFF. Carolyn reminded us of the basics of the Ancient Roman foodways. In sustaining one of the earliest metropolises ever in existence, paths of thousands of miles were constructed to intersect where grains were cultivated, so that they can be brought in to feed a mammoth population – hence the saying “all roads lead to Rome”.

To understand our relationship with nature, Carolyn highlights two different approaches: the industrial (techno-solutionist) versus the organic (natural system). The latter is of special interest to her and to the Humanizing Technology Experiment Ecoshroom. She refers to Albert Howard as the father of the modern organic movement, the first person to investigate the value of composting and how plants nourish themselves, not only through photosynthesis but also the fungal networks that form a living marketplace for micro-nutrients.

This system is fundamental to plant health. A proper fungal network will not emerge if fertilizers – which are essentially fast food for the crops – are applied excessively, resulting in weaker plants. In this sense, the notion of diet is not only relevant for humans but also for plants, to such an extent that they feed our bodies and influence our microbiome. At the same time, we witness how food is denatured by modern logistics systems that enables it to travel, and along with that other modes of transformation: from fresh to processed, from hunting and gathering to artificial intelligence optimization. Before further altering the food system, perhaps we should ask ourselves, what do we actually mean by progress?

Carolyn was surprised at how much food features in different models of Utopia, a multidisciplinary approach to look at where we evolve, in a good place or no place, and how the future might be. From the model of the Republic by Plato to Ebenezer Howard’s pursuit of limiting growth and effectively recreating Economía, there have been many endeavors attempting to answer how the countryside and the city can be brought together. The crux of the matter is to put food back into the center of our lives – it should not be a cheap product at the fringes of our concerns.

“We created an illusion of cheap food through externalizing the true cost of production. There is no such thing as cheap food.”

People in the 21st century often mistake “good life” as having food available in large quantities, while in reality we might be better served to move at a slower pace – if not in reverse gear – in food production, focusing on quality instead. That involves, as Carolyn mentioned, mob grazing, no-till to stimulate complexity and nutrients underneath the soil, forest garden or rewilding with agroforestry. All of us needs to appreciate that time is life. Natural integration through less intensive methods fosters societies in which human and non-human flourish. That also means we have access to quality food, the essential ingredient behind a good life.

In dealing with the highly complex food system, we are faced with different questions and options at every turn. Should we build animated public spaces to gather and share food? Do we make the choice to consume slowly? Carolyn sees two different opposing paradigms evolving: life hack versus craft. Finding brilliant tech solutions to address problems in the food system and attain sovereignty; or rediscovering the manual and the organic, sharing simple food jointly from an Epicurus approach to a good life. Of course, there are many positions in between. All such questions should be fed into a greater filter of how a good life would look. Carolyn leaves us with the conclusion that there is no silver bullet, but keeping a rich food culture is the best way to live in a diverse terroir.

Written by our consortium partners Lija Groenewoud – van Vliet (In4Art) and Vincent Leung (Carlo Ratti Associati).

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement 101069990.