What’s the right supply chain for urban food? ○ Reflection article – HUNGRY ECOCITIES

What’s the right supply chain for urban food?

Based in the heart of Barcelona, the company InstaGreen has been working on small-scale controlled environments since 2015 to grow microgreens. Initially started as a microgreens grower for local shops and restaurants, the company changed its focus a few years ago and now concentrates on developing low-energy and affordable growing units, which they sell to urban growers all around the globe, packaged with tailored training and advice.

There are many obvious benefits to growing food locally and nearby consumers: It allows cutting down emissions from transport, knowing the growing conditions, and enabling the consumption of fresher and nutrient-rich foods. However, InstaGreen wondered whether a one-size-fits-all supply chain model is appropriate for all food types because distance alone doesn’t determine ecological impact. The question popped up whether we can assess the total impact of different supply chain models for various types of food.

A truly sustainable food system must consider the full supply chain, including factors like energy use, emissions, resource consumption, working conditions, and ecosystem effects. For example, what would be better: ‘Locally grown summer fruits – in winter – from heated greenhouses’, or ‘Frozen blueberries, covered in pesticides, flown in from Chile’?

To answer such complex questions, InstaGreen proposes a comprehensive assessment tool inspired by frameworks like the Doughnut Economy—one that evaluates multiple layers of impact. Developing this tool, however, will require collaboration beyond InstaGreen alone.

When we look at the total impact, what supply chain model is optimal for which food type?

Enter Hungry EcoCities. In 2024, InstaGreen decided to join our EU-funded innovation project to push their knowledge and capabilities as a developer of small-scale, low-energy indoor farming systems for crop cultivation. Following a call and selection process, the team behind Hungry EcoCities, consisting of creative studios, researchers, and innovators, offered InstaGreen a spot in the project. Since then, and until October 2025, InstaGreen will be at the heart of a series of innovation experiments. Involving artists, scientists, students, and studios, they are working on exploring and prototyping answers to their most pressing questions. One of their most pressing questions is the one raised above.

Prof. Robert Boute is a professor in supply chain management and digital operations at KU Leuven and Vlerick Business School. He is one of the researchers in Hungry EcoCities. He was intrigued by the question raised by InstaGreen, and together, they decided to try to find answers with the help of the postgraduate Master’s students in Management at Vlerick Business School. The students were asked to propose a recommendation model that looks at the total impact to advise an optimal supply chain model for different food types. In this article, we highlight the most surprising and interesting conclusions and insights that came out of this work.

A city like Barcelona daily consumes around 950 tons of vegetables, 730 thousand eggs, 860 thousand litres of milk, 8,500 pigs, and no less than 100 thousand chickens. Where should all this food come from to ensure the city has a resilient food supply? When we look at the total impact of food, and in all of its facets, what supply chain model is the best choice for specific food types? The Vlerick students went off to chew on this question, helped with known data and inputs collected by InstaGreen and Hungry EcoCities, and came up with some interesting answers.

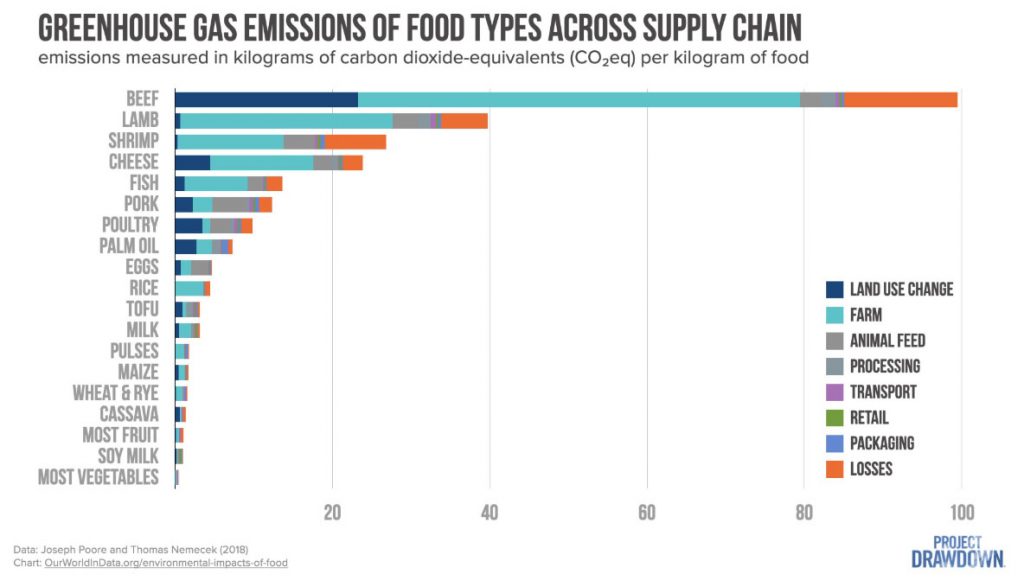

Production is the Main Driver

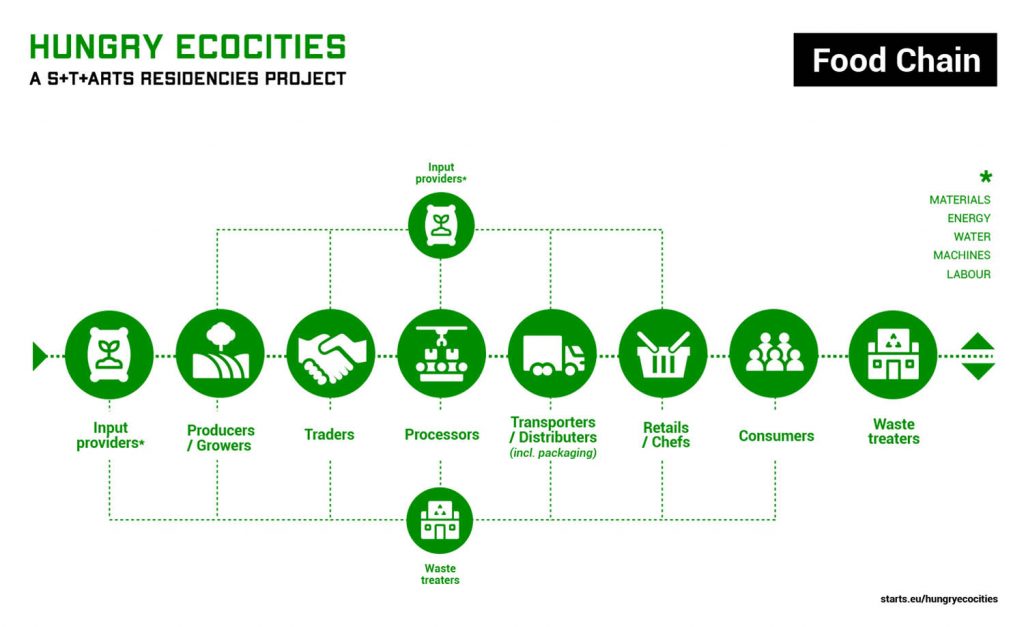

The supply chain for urban food doesn’t start in the city. It starts in fields, often thousands of kilometres away, where farmers and workers do their jobs: grow our food, harvest it, process it, package it, and send it to us. They are sending it to cities they may have never been to or heard of. The supply chain is remarkably long for many city dwellers. It is then not surprising that many people think that all of this packaging, transportation and cooling drives pollution in our food system. But this is not the case. A closer look reveals that the production phase, either on the fields, in greenhouses or elsewhere, is the main polluting driver for all food types, from grains to meat and veggies to fruits. Particularly, animal products like meat, fish, and dairy have a disproportionately high environmental impact compared to plant-based foods. This means that the most critical intervention area to achieve a better urban food supply chain lies nowhere near the city but in the fields across the globe and our dietary choices. Additionally, bringing production into urban environments doesn’t guarantee the improvements many might expect and wish for.

The Desire to Simplify Versus Embracing Complexity

When we asked the students to help us explore this question, they did what most people—including ourselves—would likely do. They began by trying to simplify the situation in an attempt to oversee and control. However, some realised this may not be the best way to go. Sure, it looks great if it seems all things are known, but in an environment as complex as urban food availability, it may be better to embrace complexity and accept that there are things we almost cannot know. One team turned this into an opportunity, highlighting that the complexity of the food supply chain goes into great detail: some trucks transporting food are not full, and the yield per field varies, not only because of climate, location or farming intensity but also because of farming strategies. And so forth. Instead of simplifying through assumptions, they prioritized flexibility and adaptability in their proposed model. Given the limits of what we can know, the models we use to simulate scenarios and test assumptions become better if they are dynamic rather than static. This way, companies like InstaGreen can build their custom version of the model, capturing reality as good as possible for their situation.

The Element of Seasonality

Specifically for fruits and vegetables, the logic of sourcing should be based on the principle of seasonality. Sourcing locally when fruits are in season, and supplementing with frozen fruits could significantly lower the negative effects of the fruit supply chain. For starters, when the offering of fresh fruits is limited to locally available types, the need for high emission air transport of non-seasonal fruit imports would fall away. In addition, seasonal fruits need less refrigeration, demanding less energy. Labor ethics, land use, and water use would also benefit from reducing our addiction to non-seasonal, non-geographical, fresh fruit. Reorganizing our fruit supply chain around the principle of seasonality offers a promising starting point for developing more sustainable fruit distribution systems. While consumer demand for year-round access to summer fruits would likely persist even with limited availability, shifting market norms through education and offering appealing seasonal alternatives could gradually help reorient consumption patterns toward more sustainable choices.

The Story of a Poke bowl

Have you ever seen someone eating one ingredient at a time? Choosing just rice for breakfast, just vegetables for lunch and only fish for dinner? No, people do not eat ingredients; they eat meals. To make things even more complicated, when we think about the urban food supply chain and follow the line from field to fork, it only makes sense to do this at the dish level. After all, proudly sourcing tomatoes from one’s own garden can be easily overshadowed by the avocado lying next to it, responsible for South American deforestation. In comes the story of the Poke bowl. A dish containing a wide variety of ingredients, the Poke bowl is an interesting metaphor for developing a vision on a supply chain sweet spot for urban food. Tracing all the ingredients one by one, the Poke bowl based on farmer market beef (best balance between sustainability and working conditions), rice from the supermarket (best for bulk foods), locally sourced avocado (getting them from overseas comes with a lot of issues), farmer market field grown tomatoes and supermarket green beans is the current sweet spot when balancing emissions, ethics, price and convenience. It’s worth noting that substituting beef with plant-based protein would substantially reduce the bowl’s overall environmental footprint, highlighting how our food choices—particularly regarding animal products—can significantly impact sustainability.

The Underperformance of Supermarkets

Who doesn’t buy food at supermarkets? They have become so dominant in our day-to-day sourcing of our meals that most people don’t think about how they perform in comparison to local markets in terms of emissions, price, freshness, social justice, and use of resources when it comes to the impact associated with the food they offer. In this project, this question was asked by multiple teams working on the case, all reaching a very similar conclusion: supermarkets underperform compared to local markets on emissions (significantly higher), healthiness (significantly less fresh and nutritious offering), social justice (significantly more issues with labor and safety of producers), and resources (significantly more use of energy and water across the board). They perform better than local markets only on price, making them cheaper, but often only slightly. So, when it comes to choosing where to buy, if we are serious about a better food supply chain and our health, we may want to empower local markets over supermarkets.

In Conclusion

The world is represented in a single meal, with all of its beauty (richness of ingredients, tastes, cultivation technologies, global collaborations) and its ugliness (extractive practices on people, soils, resources). The only way to eliminate the ugliness is if we accept that fairness must come before convenience. Sometimes, products are simply not available because the season is not right. That culinary creativity should lie in working with scarcity, rather than abundance. We need to normalise agricultural practices in daily life for more citizens, which is essential to realise the full potential of local and home-based food production.

To support, the students developed various models that can help give balanced recommendations. To have less negative impact, we must make different, less convenient choices than we do now. InstaGreen follows these guidelines: First, eat less meat, fish and dairy. Second, eat what is locally available that season, grown through sustainable practices (organic, regenerative farming). The best way to find this food is not at the supermarket, but at local farmers’ markets.

Due to the complexity of our food system, it is very hard for people to make sustainable decisions about their food. Awareness of key factors—such as production methods, transportation emissions, seasonality, packaging waste, labor ethics, and water usage—and how these environmental and social impacts compare with one another is very much lacking in society. Whilst acknowledging this complexity, it is helpful to digest the available data to simplify and visualize these impacts across the entire supply chain. That way, people can make better informed choices about what they eat, where they source it from, and when certain foods are most sustainable to consume.

Insight from the Professor

This was an excellent experience for the students. They had the opportunity to work on a real business challenge with no obvious solution. Although students find this initially challenging, it prepares them for the “real world”. Also, by developing a comprehensive model (and feeding it with data), it became evident that there is no one-size-fits-all solution and nuance is needed.

With thanks to the Master students of Vlerick Business School, class of 2025.

Charles, Emma, Shield, Jarne, Marthe, Pieter-Jan, Aymane, Jeewat, Berten, Lorien, Milind, Marius, Stien, Janne, Damira, Lucas, Siavash, Lyn, Ewout, Lara, Heloise, Lucas, Floris, Justin, Emile, Pauline, Khalil Ahmad, Thomas, and Linh.

Article written by Rodolfo Groenewoud-van Vliet (In4Art), Anneke Stolk & Remko Dirkmaat (InstaGreen) and Robert Boute (KU Leuven and Vlerick Business School).

The HungryEcoCities project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement 101069990.