The S+T+ARTS4Water II Summer School, held in May 2025 in Rijeka, Croatia, set out to bring together artists, researchers, and experts in technology to collectively explore the complexities of port ecosystems.

The Summer school was planned by a task force of project partners led by PiNA to offer an interdisciplinary environment where artists, experts, and stakeholders come together to reimagine ports as resilient, forward-thinking ecosystems. Ports serve as dynamic spaces where industrial, ecological, biological, and community interests converge. By examining the multiple intersections that shape port environments, participants were invited to envision new ways to strengthen climate resilience, foster sustainability, and support systemic change.

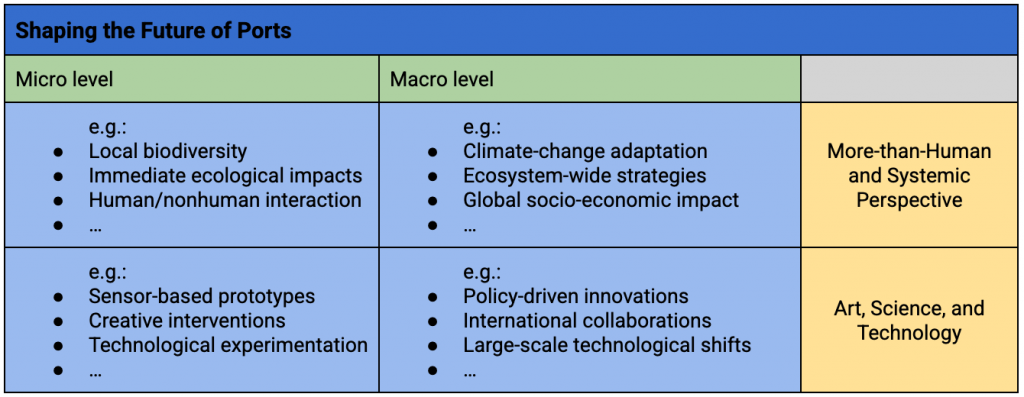

Envisioned as pivotal gateways for global trade, ports are far more than merely logistic hubs; they are dynamic and interlinked ecosystems where industry, biodiversity, and communities meet. Grounded in a two-axis matrix (1) Micro vs. Macro and (2) More-than-human perspectives, Interconnections, Climate change, and Art/Science/Technology-driven innovation—the Summer School invited participants to see ports both from the inside out and the outside in.

- Micro Level

At the Micro level, the everyday life of harbors is uncovered, focusing on water quality, local biodiversity, and how shipping, dredging, and industrial processes affect both human and nonhuman stakeholders (marine fauna, seabirds, microorganisms). This close-up lens highlights the immediate intricacies of port operations and underscores the importance of sustaining diverse life forms in a tightly shared environment. - Macro Level

By extending the gaze, the Macro level places these localized dynamics within wider local and global frameworks—from trade flows and coastal resilience to international climate negotiations and the socio-economic well-being of port communities. Ports thus emerge not as stand-alone industrial sites, but as nested nodes where the well-being of river systems, maritime routes, and neighboring regions are intricately connected. - More-than-Human and Systemic Perspectives

Recognizing ports as ecological interfaces, illuminates how all living entities and processes interrelate within these environments. In the face of climate change, such a systemic approach reveals shared vulnerabilities and the pressing need for innovative, adaptive strategies. - Art, Science, and Technology

Bridging art, science, and technology unlocks creative, holistic responses—whether through sensor-based prototypes, speculative artworks, or policy-driven interventions. Collectively, these overlapping views form a fertile ground to envision ports as collaborative, future-facing ecologies.

The Summer school approach was rooted in proven methodologies of interactive experiential learning. Throughout the duration participants were encouraged to draw on their own experiences, expertise, and insights, and to blend them with those of others. This collective learning environment aimed to stimulate meaningful reflection on the overarching theme of “Shaping the Future of Ports.”

- Experiential Learning: Real-world case studies, site visits and hands-on group activities fostered active engagement and deeper understanding.

- Peer-to-Peer Exchange: Reflecting the principles of non-formal education, the Summer School was structured as a space to exchange knowledge, skills, and experiences—not merely to host presentations. While individual work may arise naturally, our primary objective was to combine participants’ competencies for creative, future-oriented solutions.

- Reflective Processes: Guided discussions, facilitated reflection sessions, and feedback loops ensured every insight—be it technical, creative, or conceptual—collectively informs the path forward.

Date: Tuesday, May 12 – Friday, May 15 (3 days) + May 16 (+1 Open day)

Location: Rijeka, Croatia / Rijeka City Library and the cultural venue Children’s House.

- Day 1: Opening session featuring a keynote speech, introductions, and initial networking activities.

S+T+ARTS4WaterII Summer School Opening at Rijeka – keynote speech Srečko Horvat

- Day 2: Collaborative group work on a large-scale roadmap, guided by systems thinking and expert contributions.

- Day 3: Scenario planning for future solutions and finalization of the roadmap, culminating in an evening networking event.

- Day 4 (Open Day): Visit to the port of Rijeka, interactive sessions, and local workshops.

Participants investigated ports from multiple vantage points, zooming in on immediate operational details (water quality, biodiversity, industrial impacts) and zooming out to broader socio-economic and environmental contexts(community well-being, trade flows, climate negotiations). The two-axis matrix—Micro vs. Macro, plus more-than-human perspectives, interconnections, and art/science/technology innovation—frames these explorations. Emphasizing climate resilience throughout, the program challenged everyone involved to envision sustainable futures for ports and the broader water systems they interconnect.

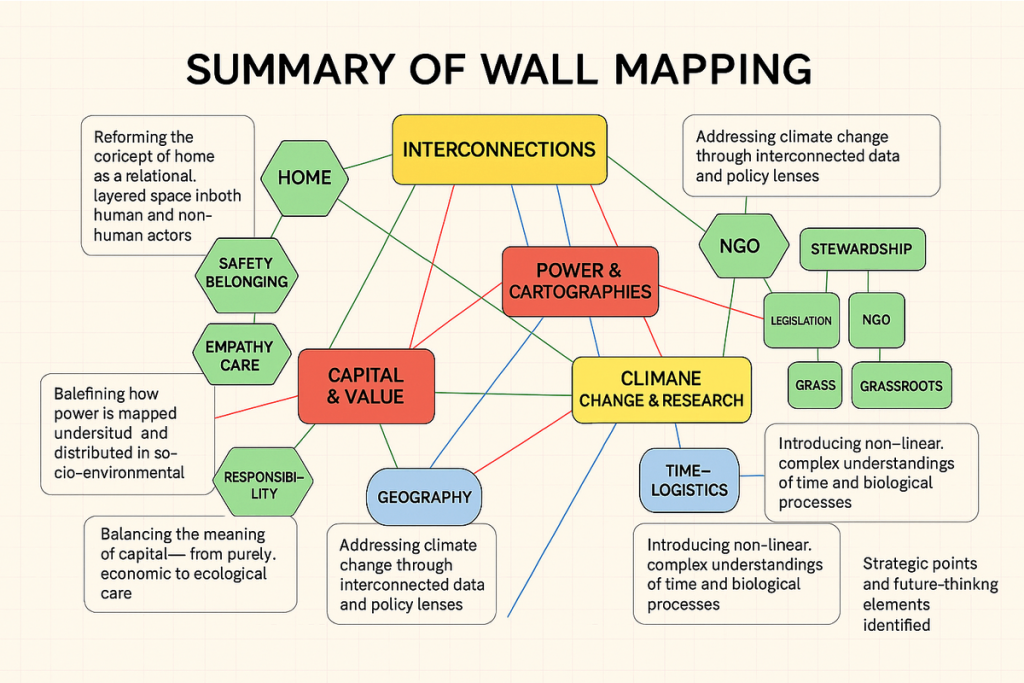

The collective efforts of participants generated a strategic roadmap for the future of port ecosystems. This roadmap serves for multiple purposes—shaping policy recommendations, guiding artistic interventions, and fostering community-led actions. In this way the Summer School outlined the foundational principles needed to catalyze innovation, resilience, and sustainability in ports worldwide.

One of the central reflections arising from the Summer school spotlighted the inherent challenges of interdisciplinary cooperation. While all participants shared a commitment to addressing pressing ecological and social issues, they approached the work with markedly different epistemologies. Experts frequently grounded their contributions in data, empirical analysis, systems thinking, and structured methodologies. In contrast, artists worked through metaphor, speculative imagination, and experiential inquiry. These divergent approaches created initial friction, particularly around expectations for outputs and further exploitation.

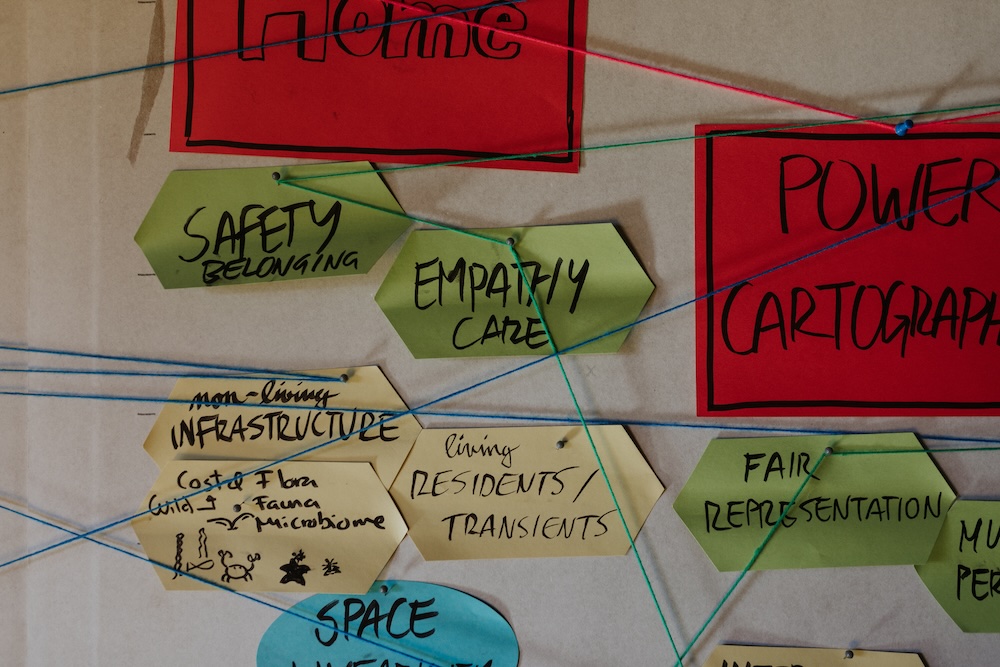

The use of systems thinking and visual mapping brought the opportunity to mediate these discrepancies. By externalizing ideas on a shared canvas, groups were able to surface interdependencies that cut across disciplinary logics. For instance, mapping exercises revealed how biodiversity, industrial processes, and community life intersect within ports, enabling participants to consider both micro-level dynamics (e.g., water quality, dredging, and local livelihoods) and macro-level frameworks (e.g., global trade flows, climate negotiations, and coastal resilience). This dual lens encouraged participants to see beyond disciplinary silos and to identify synergies that are otherwise not apparent.

Another key challenge lay in the semantic terrain. Terms such as innovation, ecosystem, or port carried different connotations depending on disciplinary perspective. For technologists, innovation was often framed in terms of efficiency and infrastructure. For artists, it is related to cultural transformation and reimagined relationships. Researchers tended to emphasize measurable impact and evidence-based validation. Structured dialogues, such as the world café sessions, allowed participants to unpack these differences and work toward a shared, though provisional, vocabulary.

Rather than being resolved, these frictions were embraced as productive. The Summer school demonstrated that bridging disciplinary worlds is not about arriving at consensus but about cultivating a capacity for dialogue across difference and building the concept of art thinking as a potential innovative approach across disciplines. The coexistence of speculative models, empirical data, and technological prototypes revealed the potential of hybrid approaches. Artists’ speculative scenarios challenged researchers to reconsider overlooked variables, while scientists’ ecological mapping grounded artistic interventions in systemic realities.

In reflection on the experience, it is clear that interdisciplinary collaboration requires patience, humbleness, and a willingness to engage with discomfort. The Rijeka Summer school provided a framework within which these qualities could be practiced. Its significance lies not in the production of definitive solutions but in the creation of a community of practice capable of carrying forward the dialogues initiated and bringing art thinking into different spaces.

For future iterations, two recommendations stand out. First, building in additional time for translation—both linguistic and methodological—would further support mutual understanding. It is equally important to ensure that participants from technology, science, support institutions, producers, curators, and artists are equally represented. Only in this way can the starting point of interdisciplinarity, which is a prerequisite for finding synergies at the intersection of science and art, be ensured. Second, providing more explicit opportunities for collaborative prototyping could help bridge the gap between conceptual dialogue and tangible outcomes.

The Rijeka Summer school thus serves as a reminder that the challenges of climate change, interconnection, and more-than-human futures cannot be addressed within disciplinary confines. They demand precisely the kind of interdisciplinary resilience that emerges when artists, researchers, and technologists commit to working together, even when doing so means navigating uncertainty.

Maja Drobne, Borut Jerman, PiNA